Marx on Mexico II

It has often been thought that Marx's interest in these topics occurs at the end of his life, with the Kovalevsky notebooks of 1879; however, the London notebooks of 1851 disprove this assertion.

«I have learned a great deal from the book, and with regard to the Germanic tribes enough for the time being.

Mexico and Peru I must reserve for later on [...]

After all it is no joke to summarize its rise, flourishing and decay in eight or ten pages. It is funny to see from the so-called primitive peoples how the conception of holiness arose. What is originally holy is what we have taken over from the animal kingdom - the bestial; "human laws" are as much of an abomination in relation to this as they are in the gospel to the divine law...»

– Letter from F. Engels to Karl Marx

Marx on Mexico II

For part one of the series here.

We find in Marx a clear interest in the colonial, the non-Western, the indigenous and a constant review of literature on the subject from very early in his work. It has often been thought that Marx's interest in these topics occurs at the end of his life, with the Kovalevsky notebooks of 1879; however, the London notebooks of 1851 disprove this assertion1.

A good part of the readings noted in the London notebooks are concentrated in these two works that analyze colonization in Abya Yala and its consequences in the colonial metropolises. Marx seeks this specular observation of the image of colonization on both sides: on the colonized and on the colonizer. Although he is immersed in his studies following the question of the economy separated from the bourgeois lineage, and the way in which this is transformed in concrete, material cases along with the colonial phenomenon, the reflection on what is being done to the colony takes on a peculiar mirror form that we note.

The reader will find atypical spellings (Montezuma/Moctezuma, Cuzko, Elisabeth), unfinished statements and thematic jumps that correspond to the very nature of being personal marginalia in progress (notes and summaries), not originally conceived for an edition. They are the work of a scholar in a library; in this sense, the marks and symbols in the margins of the pages made by Marx have been reproduced line by line.

Chapter IV

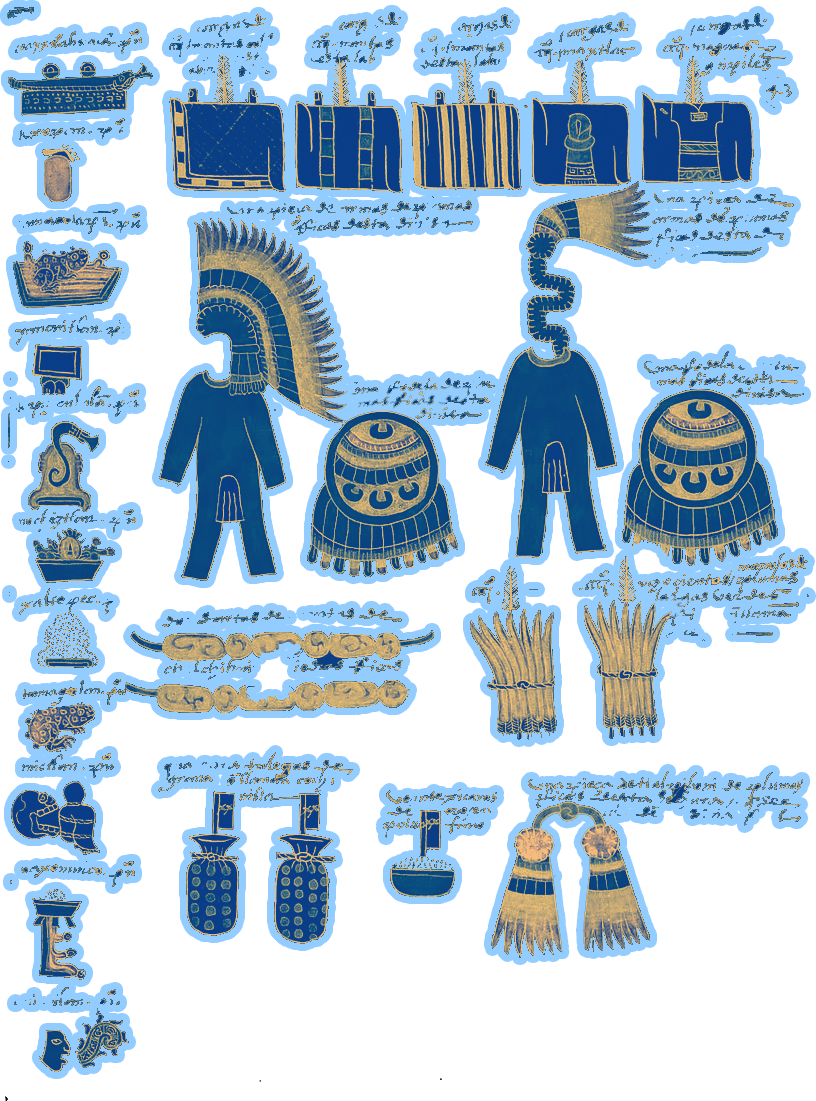

Mexican Hieroglyphs. Manuscripts. Arithmetics. Chronology. Astronomy.

Describing actions and events by tracing profiles of visible objects seems to be a natural impulse and is practiced, according to certain styles, even among the most archaic autochthones.

The use of pictograms is a higher phase, that is, to paint in an intelligible way a consecutive series of actions. But if the object of the scribe went beyond the present, the literal imitation of objects no longer responded to this more complex idea. It occupied too much time and space. It was then necessary to summarize the images, to limit the drawings to profiles, or to parts of the whole so distinct that they could easily suggest the overall idea. This representational, or figurative writing, is the most rudimentary phase of hieroglyphs.

However, these can almost never represent abstract ideas, without a model in the material world: that constitutes symbolic writing.

The third and last division is phonetic — in which the signs represent sounds — either whole words, or parts of words. Then, the series of hieroglyphs gets closer to an alphabet. Language is broken down into elementary sounds, and through it, a device is provided for expressing — in a simple and precise manner — the most subtle nuances of thought.

The Egyptians possessed all three types of hieroglyphs. The Egyptians relied almost exclusively on the phonetic type for their daily affairs, and for their written records.

The Aztecs were aware of the different varieties of hieroglyphs — more of the illustrative type than the others.

Manuscripts

Annotation 1381. In order to recognize the pictographic writing of the Aztecs it must be considered in its relation to the oral tradition, of which it was supplemental.

The material of their manuscripts consisted mainly of a fine weaving from the leaves of aloe — American agave — called maguey by the natives: a plant that grows luxuriantly on the plateaus of Mexico.

By the time the Spaniards arrived, a large number of such manuscripts had been accumulated.

The first archbishop of Mexico (the one the soldiers naturally followed), Don Juan de Zumarraga, gathered these images from everywhere, especially from Tezcuco, the great repository of that nation's archives, and then burned them in a "mountain-high pile" in the main square of Tlatelolco.

Similarly, 20 years earlier, Archbishop Ximenes burned, in a similar process of auto-da-fé2, the Arabic manuscripts of Granada.

Apart from the hieroglyphic manuscripts, the traditions of the country were collected in song and hymns, which were taught in great detail in public schools.

Mathematics

They invented a system of notation for their arithmetic, sufficiently straightforward. The first 20 numbers were expressed by an equivalent number of dots. The first 5 had specific names, while the following ones were represented by a combination of the fifth with one of the four preceding ones: 4 + one for 6, 5 and 2 for 7, etc.

The 10 and 15 each had a specific name, which was also combined with the first four numbers to express a larger quantity. These were, therefore, the characters at the basis of their arithmetic, oral in nature, as they were in the written type in ancient Rome.

The number 20 was expressed by a distinct hieroglyph — a flag.

The higher numbers were counted in twenties. When writing, they were represented by repeating the number of flags.

The square of 20, i.e. 400, had its own sign, that of a feather.

Likewise the cube of 20, i.e. 800, represented by a bag, or a sack.

This was the whole arithmetic device of the Mexicas. They used to record the fractions of large sums by drawing only a part of the object.

In this way, ½ or ¾ of a pen, or a sack, represented that proportion within the respective sums, etc. This device was not as tedious as that of the major mathematicians of antiquity, who were still unaware of the advancements presented by the pioneering Arabic or Hindu numerical systems, both of which gave a completely new aspect to mathematical science, by determining value largely through the relative position of the numbers.

The Cosmos

Their calendar year coincided with the solar year.

It was divided into 18 months, each of 20 days, to which 5 complementary days were added, to reach the number of 365.

The month was divided into 4 weeks, of 5 days each, at the end of which a public fair or market day took place.

As for the almost 6 excess hours of the solar year in the 365 days, they took care of it by adding intercalary days, not every four years as in Europe, but at longer intervals, as in some parts of Asia. They waited for 52 standard years to pass, after which they would intercalate 13 days or rather 12 ½ the delayed time.

The priests possessed a second calendar, of a religious kind, with which they kept their own records, and which regulated the festivals and seasons of sacrifices, and allowed them to make all their astrological calculations (in a great diversity of lands; the priests have attributed to the worship of the elements and of the stars a power which we, today, can scarcely conceive).

The false science of astrology is natural in societies that are in a situation of incomplete civilization. The eye of a mere child of nature observes the stars during long nights, watches carefully the changes throughout the seasons of the year, and naturally associates such change within them, as periods over which they exert a mysterious influence. In the same way, he relates their appearance to any interesting event of their era, exploring, with ardent nature, the potential destiny of the new-born child.

Chapter V.

Aztec Agriculture. Mechanical arts. Merchants. Domestic traditions. Food.

Agriculture, to a very limited extent, has been practiced by most of the rough tribes of North America. Wherever they found a clearing in the forest, or saw a fertile strip of land in an open space, or found a green bank at the edge of a river, they planted beans and corn on it.

In Mexico, agriculture was intertwined with the nation's civil and religious institutions. Everyone, except soldiers and high nobility, farmed the land, including city dwellers. The work was done mainly by men, the women being in charge of sowing the seeds, husking the corn, and the lighter labors required in the fields.

(113) When the soil was exhausted, it was left to rest. Deforestation of the woodlands. Ample storehouses for their crops.

(114) Among their agricultural products were bananas, cocoa, vanilla. The main product of this land, as in the rest of the American continent, was corn, which grew freely along the valleys, passing through the steep slopes of the Cordilleras, to the high altitudes of the plains.

Its enormous stalks accumulated sugars in these equinoctial regions and provided a sugar barely inferior to that of sugar cane itself, which was not introduced to them until after the Conquest.

However, the miracle of nature was the great Mexican aloe or maguey. Its leaves were used to make paper; its fermented sap served to produce an intoxicating drink, pulque; its leaves also served to cover the humblest houses; from its solid braided threads, coarse cloth and strong ropes were made; pins and needles were crafted from the thorns at the tip of its leaves; and the root, when properly cooked, became a pleasant and nutritious food. The agave, in short, was food, drink, clothing, and writing material for the Aztecs.

They knew and exploited silver, lead and tin. The gold, recovered on the surface or obtained in the river beds, was melted in bars or, in the form of powder, was part of the tribute given by the southern provinces of the empire. They did not know the use of iron, which was found in their soil. In spite of its abundance, it required so many processes to be developed for its use that it was generally one of the last metals to be put at the service of humans.

1391. They replaced iron with an alloy of tin and copper. With tools made of this bronze they were able to cut not only metals but also, with the help of a silica powder, the hardest substances, such as basalt, porphyry, etc. They were very skilled goldsmiths.

They used another tool, made of itztli, or obsidian, a dark and transparent mineral, which was extremely hard and found in abundance in their mountains. They transformed it into knives, blades and their serrated swords. With it, they worked the diverse stones and alabasters that were used in the construction of their public works and main edifications; the sculptures were very numerous.

They manufactured ceramic utensils for the daily tasks of domestic life. They used remarkable pigments, both mineral and vegetable. It was through them that cochineal was introduced in Europe.

They gave brilliant colors to all kinds of delicate fabrics, made with the cotton that was grown in abundance in the warm regions of the country. In addition, they possessed the art of interweaving with this the delicate fur of rabbits, etc., and then often still placed rich embroideries consisting of birds, flowers or some other original element.

The type of embroidery they took the greatest delight in was the work done with birds' feathers. The magnificent plumage of tropical birds, particularly of the parrot class, provided infinite varieties of color; and the fine quill of the hummingbirds.

Commerce and Exchange

There were no commercial stores in Mexico; the different goods and agricultural products were gathered to be sold in the large open markets of the main cities. In these cities, fairs were held every five days with great attendance from the surrounding region, to sell or buy; specific areas were dedicated to each type of article; transactions were carried out under the supervision of magistrates designated for this purpose. The exchange was carried out partly through barter and partly by means of a regulated currency of different values. It consisted of transparent cylinders of gold dust; or tin fragments, cut in a T-shape, and cocoa bags containing a specific number of beans. Peter Martyr3 (De Orbe Novo):

"O felicem monetam, quae suavem utilemque praebet humano generi potum, et a tartárea peste avaritiae suos immunes servat possessores, quod suffodi aut diu servari nequeat."

O, happy coin, which furnishes mankind with a pleasant and useful beverage and keeps its possessors immune from the hell-born peat of avarice, since your coin can not be either buried or preserved long."

Trade

There were no castes in Mexico, but the sons followed the father's trade. The different trades were arranged in guilds; each of which had a specific district of the city, with its own chief, its own tutelary deity, its own festivals, etc. The Aztecs appreciated trade.

The merchant's trade was especially respected. This position was, what we assume to be nowadays a type of itinerant merchant, whose travels took him to the remotest corners of Anahuac, and to countries beyond its borders.

He carried with him his merchandise, which consisted of sumptuous fabrics, jewels, slaves and other goods of great value. Slaves were obtained in the great market of Aztcapotzalco, a few leagues from the capital, where fairs were regularly held for the purpose of this shameful trade. Slave trade was an honorable profession among the Aztecs. They traveled in armed caravans, visited the different provinces, always carrying some valuable present on behalf of their ruler expecting another souvenir in return; along with the permit to trade.

Their government was always keen to start wars, if the merchants were mistreated, making this an excellent pretext for extending the Mexican empire. It was not unusual to allow the merchants to collect taxes, which were placed at their disposal.

It was also very common for the monarch to employ the merchants as spies to provide intelligence about the nations they visited along with information about the predisposition of the inhabitants towards their government. Then their radius of influence was wide enough for a simple merchant. They rose to high regard among the political class. Members were allowed to wear their own insignia and coats of arms. Some of them formed a finance council, at least in Tezcuco4.

The monarch often consulted them, keeping some of them always closely associated with him; he called them by the name of "uncle" — they possessed their own courts, for civil and criminal cases, although the death penalty was not excluded, when applicable; in this sense they formed an independent community, so to speak. And as their various exchanges gave them abundant stores of wealth, they enjoyed the essential advantages of an aristocratic bloodline.

Additional Annotations

(124-6) Polygamy was authorized among the Mexicans, but limited to the wealthy.

(128) The Aztecs smoked pipes and cigars and inhaled tobacco.

They were excellent appreciators of gastronomy. Sauces, sweets, etc.

However, sometimes a dish was added to their feasts, of a repulsive nature, especially when the celebration had a religious character.

On such occasions, a slave was sacrificed, and its flesh was carefully prepared to form one of the main elements of the feast.

Cannibalism, as an Epicurean science, becomes even more repulsive.

Meats were kept warm by means of plate warmers. The table was decorated with vases of silver, and sometimes gold, with a fine finish. Glasses and spoons were made of the same costly materials, including tortoise shells at times.

The preferred drink was chocolatl, flavored with vanilla and different spices.

The banquets concluded with a generous distribution of costumes and ornaments among the guests (when they retired after midnight).

The Mexica ruling class did nothing to improve the living conditions of their vassals, or to encourage their progress in any way.

Their vassals were serfs, used only to cater to their desires. They were kept in submission by military garrisons, oppressed by taxes in times of peace and by military conscription in times of war.

Unlike the Romans, they did not extend the right of citizenship to the conquered peoples. They did not merge into one large nation, with common rights and interests. They treated them as foreigners — even those in the Valley who lived practically next to the walls of the capital. The Aztec metropolis, the heart of the monarchy, felt no sympathy, neither did it vibrate in rhythm, not even a little, with the rest of the political community…

Marginalia:

Drink of choice: chocolatl, flavored with vanilla and various spices. (They did not drink it with milk).