Marx on Mexico

It has often been thought that Marx's interest in these topics occurs at the end of his life, with the Kovalevsky notebooks of 1879; however, the London notebooks of 1851 disprove this assertion.

You would be wrong if you thought that I love books. I am a machine condemned to devour them in order to vomit them up in a new form, like manure on the soil of history.

– Excerpt from a letter from Karl Marx to his daughter Laura (1868)

Marx on Mexico

We find in Marx a clear interest in the colonial, the non-Western, the indigenous and a constant review of literature on the subject from very early in his work.

It has often been thought that Marx's interest in these topics occurs at the end of his life, with the Kovalevsky notebooks of 1879; however, the London notebooks of 1851 disprove this assertion1.

A good part of the readings noted in the London notebooks2 are concentrated in these two works that analyze colonization in Abya Yala and its consequences in the colonial metropolises.

Marx seeks this specular observation of the image of colonization on both sides: on the colonized and on the colonizer. Although he is immersed in his studies following the question of the economy separated from the bourgeois lineage, and the way in which this is transformed in concrete, material cases along with the colonial phenomenon, the reflection on what is being done to the colony takes on a peculiar mirror form that we note.

The reader will find atypical spellings (Montezuma/Moctezuma, Cuzko, Elisabeth), unfinished statements and thematic jumps that correspond to the very nature of being personal marginalia in progress (notes and summaries), not originally conceived for an edition. They are the work of a scholar in a library; in this sense, the marks and symbols in the margins of the pages made by Marx have been reproduced line by line.

All these notes and summaries3 of readings deal with the colonial problem, from descriptive elements about the colony, the slave trades, internal governing differences, to the work of the Jesuits. Many of these working notes will be reflected in the Contribución a la crítica de la economía política, and in the volumes of Capital.

What is this "introduction" about? We can say that it is about Marx's concerns about the method. Where to begin?

Marx managed to accumulate an immense mass of economic studies dating back to the 1840s and 1850s. His concern seems to have been on how to set out his critical readings.

There is a clear epistemological concern, above all with respect to the considerations and readings he had made. This concern is summed up in seeking that his writing can be presented as a whole.

The aim of Marx's polemical critique was the so-called "robinsonades", which inhabited the texts of the economists of the 15th century and which were naively preserved by authors contemporary to Marx. It is the myth of Robinson Crusoe, presented as an exemplary case of the homo economicus, i.e., the belief that the individual alone, and all by herself, lies at the beginning of history:

To the prophets of the eighteenth century, on whose shoulders Smith and Ricardo still fully stand, this eighteenth-century individual - who is the product, on the one hand, of the dissolution of feudal forms of society, and on the other, of the new productive forces developed from the 15th century onwards - appears to them as an ideal whose existence would have belonged to the past. Not as a historical result, but as the starting point of history.

In this way Marx refers to the myth of Robinson Crusoe. Marx's methodological correction refers to the fact that the isolated individual simply did not exist, and that its use is a malicious way of avoiding reflection on the types of relations of human beings among themselves and, of course, on the systemic relations of exploitation and colonization. That is to say, one cannot start from this assumption, yet this is what the eighteenth-century economists and Marx's contemporaries mistakenly do.

The farther back in history we go, the more the individual - and therefore also the individual producer - appears as dependent and as forming part of a greater whole4.

Prescott. (W .H.) History of the Conquest of Mexico.

Notes on his London 1850’s tome, Chap. I: Ancient Mexico.

Climate and products. Originary races. Aztec empire.

The Ancient Mexicas or Aztecs constituted only small regions. Their land, the modern republic of Mexico. It covered probably not more than 16,000 square leagues. At its greatest extent, it could not have exceeded five and a half degrees, being reduced, as it approached its southern borders, to less than two degrees.

And yet the remarkable formation of this country is such that, although not more than twice as large as New England, it presented a great diversity of climates, and was capable of producing practically all the fruits that lie between the line of the Equator and the Arctic circle.

The regions are divided into three parts (hot land, temperate land and cold land). The cold land (plateaus) has a climate with an average temperature not lower than that of the central areas of Italy.

The land often has a parched and barren appearance, partly due to the lack of trees to protect the soil from the intense effect of the summer sun.

In the time of the Aztecs, this plateau was densely covered with larch, oak, cypress and other trees5... the curse of this barrenness can be attributed more to man than to nature. The early Spaniards waged an indiscriminate war against the forests.

The Valley of Mexico

Halfway across the continent, somewhat closer to the Pacific than to the Atlantic, at an altitude of about 7500 feet is the famous Valley of Mexico... surrounded by an imposing wall of porphyritic rock.

The landscape, once covered with beautiful greenery, with majestic trees scattered everywhere, is today often bare, white in many places, due to salt incrustations caused by the draining of the waters. The 5 lakes of the valley occupied 1/10 of its surface.

The Anahuac States

The Toltecs – the true source of later civilizations. In the 5th century, after 4 centuries, the Toltecs disappeared. Other races followed, among the most notable were the Aztecs or Mexicas and the Acolhuanos or Tezcucanos [sic], after their capital Tezcuco6 [sic].

They extended their dominion over the rougher tribes of the north. Then they attacked the Tepanecas. Then, with the help of Mexican allies, they freed themselves again, and an extraordinary race... The Mexicans also came from the remote northern regions, populated hive of nations of the New World, just as it was in ancient times.

They arrived at the borders of Anahuac around the beginning of the 13th century, shortly after the occupation of the territory by related tribes. For a long time they did not settle down, preferring to move from one place to another.

They finally reached the southwest shore of the main lakes, to settle in 1325. Tenochtitlan (Mexico) was founded; at first they lived on fish, wild waterfowl and some plants they could grow in their floating gardens (in semi-marshy areas). Such was the beginning of this Venice of the western world.

Scandals and disagreements existed among them. They gained a reputation in the region for valor and ruthlessness in war. At the beginning of the 15th century, they obtained the land from the Tepanecas for the help given to the Tezcucanos (sic).

Then took place the league between the states of Mexico, Tezcuco and the small neighboring kingdom of Tlacopán. (This country would be divided up for future wars).

By the mid-fifteenth century, under the first Montezuma [sic], they had extended from the foothills of the plateau to the borders of the Gulf of Mexico. By the beginning of the sixteenth century, Aztec dominion stretched across the continent, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, to the farthest corners of Guatemala and Nicaragua. And everywhere, with the same warrior spirit characteristic of their tradition, they found fewer tribes to fight. The history of the Aztecs is in many ways reminiscent of that of ancient Rome, not only for their military successes, but also for the politics that led to them7.

Chapter 11. Succession of the Crown: Aztec Nobility

Marx's Marginalia: Focus - Judicial system. Laws and revenues. Military institutions.

The form of government is different in the various states of Anahuac. That of the Aztecs and Tezucanos [sic] is monarchical and of an almost absolutist character.

These two nations are quite similar.

The government of the Aztecs and Tezucanos [sic] is an elective monarchy. Four of the principal nobles, chosen by their own group in the preceding kingdom, held the office of electors, to which were added, with an entirely honorary status, the two royal allies of Tezcuco [sic] and Tlacopán. The sovereign was chosen from among the brothers of the deceased prince or, failing that, from among his nephews. The choice at that time was limited to the same family. The preferred candidate had to have distinguished himself in the wars, even if he was a member of the priestly caste, as in the case of the last Moctezuma...

The succession of capable monarchs was assured in this way. The coronation of the chosen one was done after he was able to offer human sacrifices, etc. with “magnificence”, after a victorious campaign.

Nobility

The Aztec monarchs, especially towards the end of the dynasty, lived amidst a pomp of a highly barbarous… a distinct class of nobles, possessors of large tracts of land, occupied the most important offices near the person of the monarch and monopolized the administration of the provinces and cities... and 30 caciques, each of whom could gather into his domain as many as 100,000 vassals...

The country was occupied by a large number of powerful chiefs who lived in their domains as independent princes. These were required, when not residing in the capital, to deliver hostages to the leader.

These domains were subject to various types of possession and to different restrictions. Some were held without limitations, except that they could be sold to one of the plebs. Others were tied to the nobles but, in the absence of nobles, reverted to the crown. Military service was an obligation for most.

Others, instead of this service, had to take care of repairing the royal buildings and keeping the royal possessions in order, with an annual offering, by way of tribute, of fruits and flowers... (Marx's emphasis: In all this there are many features of the feudal system.)

Despotism

The kingdoms of Anahuac, in spite of their despotic nature, knew in reality several circumstances that attenuated it and that were unknown in the Eastern despotisms. The legislative power in Mexico and Tezcuco was completely in the hands of the monarchs.

On the other hand, the constitution of judicial tribunals. These were more important for provincial people than the legislative authority. In each principal city with its independent territories stood a supreme judge, appointed by the Crown, with original and final jurisdiction in civil and criminal cases.

No appeal against his sentences, except before the Crown. The position was for life and whoever usurped its symbols was punished with death. He was known as cihuacoatl. Under his command, in each province, a court of 3 members.

Apart from these courts, there was a body of magistrates distributed throughout the country, chosen from among the people themselves in the different districts. Their authority was limited to minor cases.

There was still another class of subordinate officials, chosen from among the people themselves, composed of a certain number of families, charged with watching over and reporting any disturbance or breach of the law to the higher authorities... the law allowed appeal to a higher court only in criminal matters.

The penal code was extraordinarily severe. The judges of the superior courts received for their work a share of the royal lands, reserved for this purpose. These, as well as the supreme judge, were kept in office for life.

Law and Punishment

The laws of the Aztecs were recorded and shown to the people in their hieroglyphics. The greater part of them, as in the case of every rustic nation, is concerned more with the safety of persons than with property.

All great crimes towards the capital of society. Even the murder of a slave was punishable by death. Adultery with stoning.

Theft with slavery or death. But this crime was not very feared, since the entrances of the houses did not have locks or locking systems of any kind.

Intemperance in younger people was punishable by death and in the case of older people by loss of status and confiscation of property.

Marriage rites were very ceremonious. Special courts for marriages. No divorce was possible.

Slavery

Slavery. Different types and levels. Prisoners of war, almost always destined for sacrifices; criminals, debtors, persons who, because of their extreme poverty, voluntarily gave up their freedom, and children who were sold by their own parents.

For these voluntary sales, the services that could be demanded were determined with great precision. The slave was allowed to have his own family, own property and even own other slaves. His children were free.

No one was born a slave in Mexico.

Masters often freed their slaves in their wills. Also with their marriages. But an insubordinate and violent slave would be taken to the market with a noose around his neck and there he would be sold publicly a second time, reserved for sacrifice.

Royal revenues came from different sources. The extensive royal domains made their payments in kind. Places close to the capital were obliged to provide men and materials for the construction and maintenance of the royal palaces, exploited labor. They were also to provide fuel, provisions and whatever was necessary for their household expenses.

The principal cities, those that had several villages and vast territories under their dependence, were divided into districts. The inhabitants paid a determined part of their production to the crown.

The vassals of the great chiefs also paid a part of their income to the public treasury - very similar to the (financial) regulations of the ancient Persian empire.

Calpulli or the commons

The people of the provinces were separated into calpulli or tribes, and held the lands around them in common.

Officials by choice divided these lands among the many families of the calpulli and, when a family died out or left, their lands returned to the common pool to be redistributed.

The individual landowner had no power to alienate such lands.

The laws dealing with these matters were very precise, and had been in existence since the occupation of the country by the Aztecs. Apart from this tax on the agricultural production of the kingdom, there was another on its manufactures. For example, cotton clothing and feather cloaks, decorated breastplates, gold vessels and trays, gold powder, bands and bracelets, crystal, painted and gilded jars and chalices; bells, weapons and utensils of copper; paper fans, grains, fruits, copal, amber, cochineal, cacao, wild animals and birds, wood, lime, mats, etc., salt, leopard skins, etc.

Garrisons were established in the major cities, probably in the most remote ones and in those that had been recently conquered, in order to reduce any revolt and to guarantee the payment of tribute.

The authority of the chieftains, subdued by the allied armies, was generally confirmed and the places that had been conquered were allowed to retain their laws and customs.

Tax collectors

Tax collectors traveled throughout the country, easy to recognize thanks to their official insignia, and feared for the ruthlessness of their exactions.

Debtors could be taken and sold as slaves. In the capital there were huge granaries and warehouses to receive tribute. An official in charge of receiving the tribute lived in the palace... he possessed a map of the whole empire, with a meticulous detail of the taxes estimated for each part of it. These taxes, initially moderate, ended up being overwhelming towards the end of the dynasty and this burden through the collection of taxes provoked a rejection throughout the country that would pave the way for the conquest of the country by the Spaniards.

Communication

Communication with the most remote parts of the country was through messengers. Every two leagues of distance, there was a mail station for these messengers. The messenger, along with his message encoded in hieroglyphics, ran with it to the first station, where the message was passed on to another messenger, and so on. These messengers, trained from infancy, traveled with incredible speed, so that these messages were carried at a speed of between 100 and 200 miles per day.

By this means, information about the movements of the royal army was carried swiftly to the court... as was the case in ancient Rome, in Persia. In China the stations were three miles apart. But these stations were for the exclusive use of the government....

War

In Mexico, as in Egypt, the soldier shared with the priest a high consideration. The tutelary god of the Aztecs was the god of war.

Every war was a crusade to obtain sacrifices for the god of war. The fallen warrior went directly to a region of ineffable joy in the shining houses of the sun.

From the beginning of hostilities, ambassadors were sent to demand that the enemy state adopt the Mexica gods and pay the traditional tribute. Precise amounts were extracted from the conquered provinces, which were always subject to military service and the payment of taxes; and the royal army began its march, generally with the monarch at its head. There is a remarkable resemblance between these military traditions and those of the ancient Romans... with various military orders, each with its particular privileges and insignia.

In addition, a kind of knighthood, of a lower level; the lowest reward for military prowess; he who had not yet attained it, could not wear ornaments on his arms or person, and was obliged to wear a coarse white cloth, made from the threads of the aloe, called "nequen".

The members of the royal family themselves were not exempt from this law. The dress of the higher level warriors was picturesque and often splendid. Their bodies were covered with a tightly padded cotton cloak, thick enough to be impenetrable to the light projectiles of indigenous warfare.

The wealthier chiefs sometimes wore, instead of this cotton mail, a breastplate made of thin plates of gold or silver. Over this mantle they wore a surcoat made of magnificently arranged feathers, a work in which they excelled. Their helmets were often made of wood and sometimes of silver, modeled to resemble the heads of wild animals. At their tips waved plumes of multicolored feathers, to which were added precious stones and gold ornaments. They also wore necklaces, bracelets and earrings, made with the same sumptuous materials. Banners with gold embroidery and feather work. The battalions and the great chiefs also had banners and appropriate equipment... war was for them a trade, although not yet a science. The value of a warrior was appreciated according to the number of his prisoners and no ransom was sufficient to save the consecrated captives.

Their military code was naturally also draconian. Hospitals were established in the capital for the cure of the sick and as a permanent refuge for invalid soldiers, with physicians to care for them. It is thus that the Aztec and Tezcucan [sic] tribes advanced in their civilization quite far, far above the wandering tribes of North America.

The American Indian possesses something particularly sensitive in his nature. This type of sensitivity instinctively shrinks from the rough touch of a foreign hand. Even when this foreign influence comes in the form of “civilization”, he seems to sink and languish under it. Such has been the case with the Mexicas... the moral characteristics of the nation, all that constituted its individuality as a group, obliterated forever.

Chapter III. Mexican mythology

Annotations: Priestly orders and temples. Human sacrifices.

The Mexican religion was not in its first phase. It adopted a particular complexity as a result of the priests, who had compiled a more meticulous and difficult form of ceremonial than that of any other nation, past or present.

The Aztecs had inherited a more clement religion from their ancestors, upon which they grafted their own mythology8. The latter became dominant and imparted a dark hue to the amendments of the conquered nations, which the Mexicas, like the ancient Romans, seem to have incorporated into their own, until the same funerary superstitions became established even to the remotest limits of Anahuac.

Huitzilopotchli (the Mexican Mars) was above them all. This was the superior god for the nation. The fantastic forms of the Mexican idols were symbolic to the highest degree. Huitzi…–etc. had been born of a virgin (like Buddha (India), Fuxi (China), Shaka (Tibet).

On the altars of every city of the empire one could perceive the stench of human sacrifices...

The legend of the foreign god Quetzalcoatl opened the way for the conquistadors.

These Mexica gods ascended hierarchically from the Penates or household gods, whose small images were found in the humblest homes. In their funeral rites we find similarities with Catholic, Muslim, Tatar, ancient Greek and Roman ceremonies.

Baptisms... (as with the Christians, also to wash away sins).

The priestly caste

The priests sought to impress the imagination of the people with the most formal and pompous ceremonials.

The influence of the priestly caste is maximal in this imperial state of civilization, where it encompasses all the scanty science of its time in its own body.

It is particularly the case, when this science does not deal with the natural phenomena of existence, but with the extravagant chimeras of human superstition.

Thus, the sciences of astrology and divination, in which the Aztec priests were initiated – seemed to hold the keys to the future in their own hands.

The priestly caste was very numerous; 5000 priests were attached to the main temple in the capital. The different ranks and functions of this body were hierarchically organized. The most musical ones directed the choirs. Others organized the festivals according to the calendar. Others were concerned with the education of the young and others dealt with hieroglyphics and oral traditions; while the somber sacrificial rites were reserved for the high dignitaries of the order. At the apex of the whole body of priests, two high priests, chosen by the monarch and the principal nobles; inferior only to the sovereign.

Each priest was devoted to the service of a particular deity, and they lived in spacious quarters in their temples; otherwise, they were authorized to marry. Many prayers, vigils, fasts, scourging, and mortification of the flesh. The priests were distributed in parishes. As in the case of Catholics: confessions and absolutions.

The absolution of priests was accepted in lieu of legal punishment for offenses and authorized exculpation in case of arrest. For education, some buildings were reserved inside the main temple. In these convents (cloisters?) the young men and women were instructed.

Land was attached to each temple for the maintenance of the priests. Under the last Moctezuma, they covered every district of the empire. Additionally, this religious order was enriched by the delivery of the first fruits, etc.

The surplus of what was dedicated to the support of the worship was distributed to the poor.

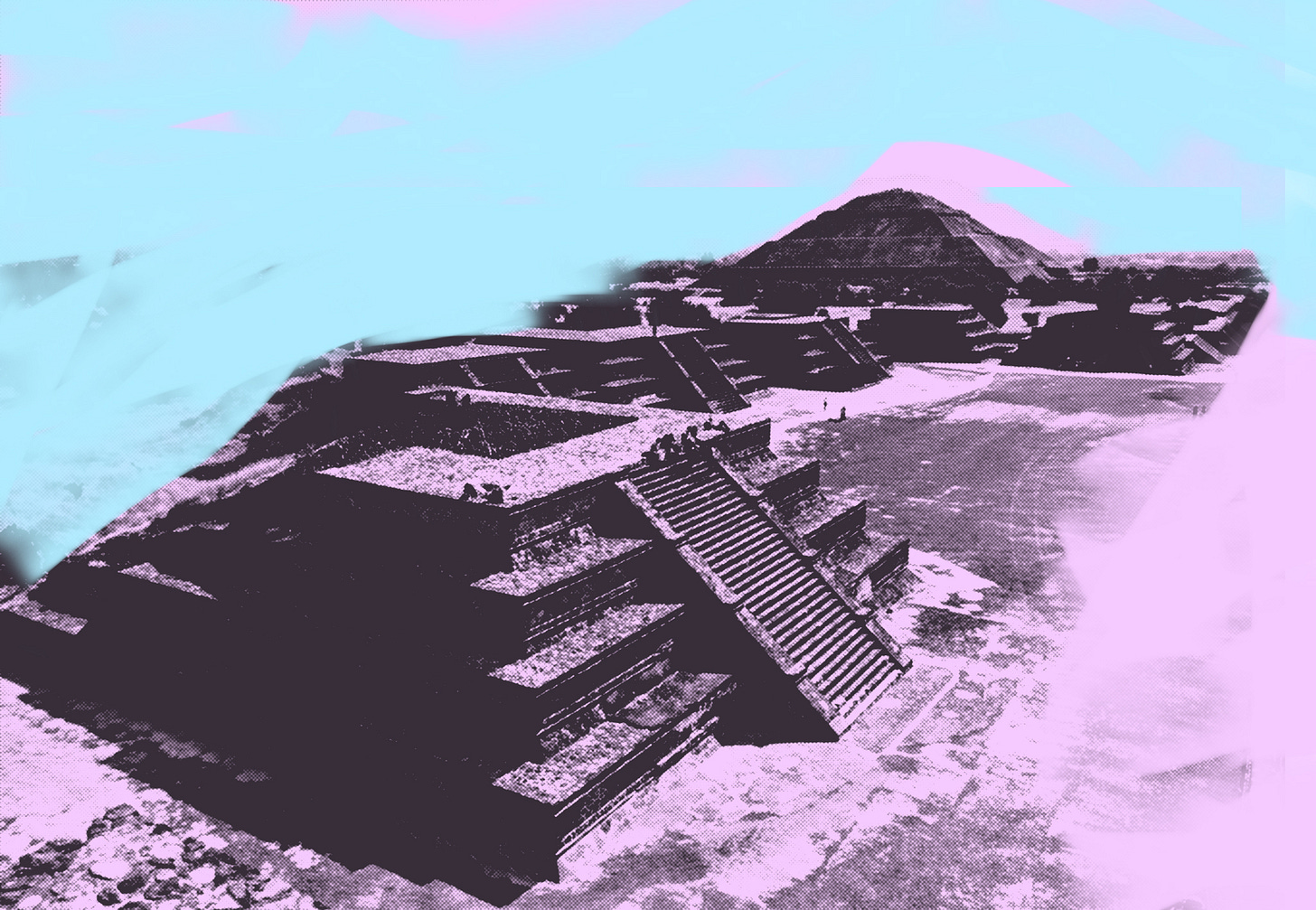

Very numerous temples. Throughout the buildings themselves (specifically on the steps around the pyramids, on the altars, etc.) all religious services were public.

The long processions of priests, rising on their massive flanks, as they ascended higher and higher to the summit, the horrible sacrifices celebrated there, were visible from the farthest corners of the capital.

Human sacrifices

Human sacrifices among the Aztecs were admitted at the beginning of the 14th century, two hundred years before the Conquest. At first they were infrequent; they increased with the extension of the empire; eventually, every festivity ended with this abomination…

Often, in these sacrifices, the choicest tortures were rigorously prescribed in the Aztec ritual. Rather well described in Dante's Canto XXI9. These creations of the Florentine poet's fantasy almost acquired life at the same time he was writing them, through wild and unknown beings in an unfamiliar realm. On some occasions, women and children were also sacrificed.

The body of the captives was given to the warrior who had captured them in battle, then presented for the amusement of his friends. These consisted of banquets filled with delicious drinks and delicate meats, artfully prepared and attended by people of both sexes.

Nowhere else did human sacrifices exist on the scale of Anahuac. Between 20 and 50 thousand sacrifices per year. On great occasions, such as the coronation of a monarch or the consecration of a temple, the number was even more frightening.

There was a tradition of preserving the skulls of those sacrificed, in buildings destined for this purpose. The dogs of the priests (xoloitzcuintli) were convinced that the only food for their idols was the heart of human beings. The great war objective of the Aztecs also consisted in the capture of victims for their sacrifices, as well as the extension of their empire.

The influence of these practices, the familiarity brought about by the bloody rites of sacrifice, provoked a thirst for massacres on the part of the Aztecs, similar to that which the exhibitions in the Circus whipped up in the Romans.

The constant recurrence of the ceremonies, in which the people took part, associated religion with their innermost concerns, and diffused the darkness of superstition over the hearts of the households: the very character of the nation had assumed a grave and melancholy aspect.

The priests became more and more powerful. The whole nation, from peasant to monarch, bowed before the tyranny of fanaticism. But one should think of the Inquisition in the sixteenth century. During the infamy of the Inquisition, this world was inextricably tied to the enduring doom of the other....

The civilization that the Mexicas possessed came from the Toltecs, a nation that never stained its altars with blood. Everything that could merit the appellation of scientific understanding in ancient Mexico came from that source.