Magonista is but a mere word

While the State commemorates the 100th anniversary of the death of Ricardo Flores Magón, in his hometown, Eloxochitlán, the ideals of the Oaxacan anarchist seem to have been buried by politicians.

Magonista is but a mere word

While the federal government commemorates the 100th anniversary of the death of Ricardo Flores Magón, in his hometown, Eloxochitlán, the ideals of the Oaxacan anarchist seem to have been deliberately muddled by local politicians and caciques, the local political leaders.

Regardless, there are still libertarians out here who, from their trenches, fight against this oblivion, to salvage the memory of revolutionary struggle from and for the Mazatec people.

And one of them is Carrizo Trueno1.

ELOXOCHITLÁN DE FLORES MAGÓN, OAXACA - Carrizo Trueno walks slowly. He opens a small wooden gate that, in the background, reveals a house; his house. He smiles and shakes hands. Then he adjusts his hat and, without haste, firmly buttons his shirt.

"Good morning," he says.

Behind him, the Mazateca mountain range reveals a majestic forest, as the warm rays of the sun lightly caress the canopy of the trees. The cold weather, typical of this mountainous area, has given way to the warmth that precedes the rains.

We are in Eloxochitlán de Flores Magón, where Ricardo Flores Magón was born.

Carrizo Trueno is also from here, and the several generations that comprise his family were born in this community. His name, in reality, is not Carrizo, but he prefers to be called that way. He is a painter, musician, sculptor, writer and a libertarian, like Ricardo Flores Magón.

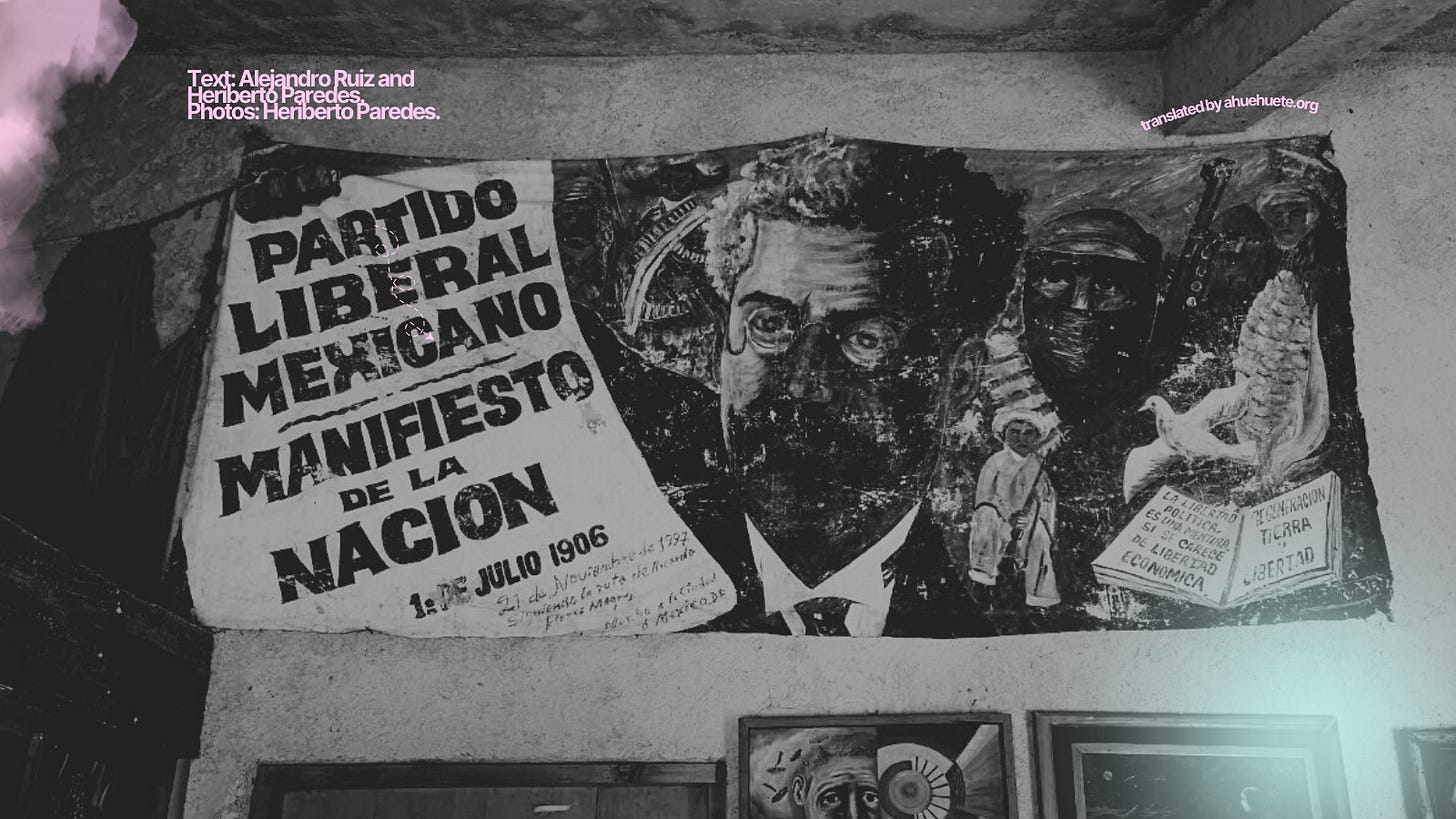

"We'll put some coffee on now," he says, as he opens the door to his studio. Upon entering, a pile of books and dozens of paintings adorn the path. In some of them, Ricardo appears, surrounded by Mazatec children, townspeople, and the huehuentones2 of the festival of the dead. In others, you can spot the faces of peasants tired of working the land, reading a book, or Regeneración, "the one by Flores Magón, not Morena3," clarifies Carrizo.

"Those were the people Ricardo was fighting for," he adds, as he sets up a couple of chairs to tell his story. The story of a freedom fighter in the Mazatec highlands.

I'm going to sing a corrido

Before talking, Carrizo pulls out a guitar. He sings revolutionary folk tunes that recall the guerrilla fighters who strove for the freedom of the masses. His brother, also a libertarian, arrives in the room with his guitar.

"We wrote a corrido to Ricardo," says Carrizo, as he picks up his instrument.

"An anarchist shining / emerged over there by the mountains / in the Mazatec Sierra / the land of mazate4," say the first lines. Then they tell the story of Ricardo Flores Magón, his brothers and his parents and how Carrizo came to know the Mexican anarchist:

To know Magón's story must have been, a little bit, our way of living too. That does not mean that people did not live, as I have lived. The physical suffering over the lack of many things, economically and potentially intellectually as well. In my time I went to school, I learned very little, but then I went out into the world. I went out to many towns, many places, many cities and there I met many people.

They recall when the anarchist was imprisoned by the government of Porfirio Diaz, after founding his newspaper and promoting his ideas among workers and peasants throughout the country, which leads to a reflection on when he was imprisoned by the U.S. government. The story of Flores Magón, told by Carrizo and his brother, relates to the fate suffered by hundreds of revolutionaries: prison, and death.

In Eloxochitlán, a hundred years after these stories, things do not seem very different; for, although the revolution triumphed, in this small town in the Sierra Mazateca, opponents of the State, no matter what color the government may be, continue to be imprisoned.

The political parties, for their part, have contributed to the destruction of the organs of collective autonomous organization that, for centuries, have governed life in Eloxochitlán. Of the communal assembly not much is left, and what is left has been co-opted by the State.

The guitars fall silent.

Carrizo takes his chair, takes a sip from his glass of water, and clarifies his position on Magonista thought and his personal adherence.

"I don't consider myself a Magonista, because Magón himself says that when you call yourself a Magonista, you are creating a boss, a leader.

Magonista is just a word, but what is perceived is the question of political vision, how to act, and how to struggle, and that would be an integral component of it.

I consider myself instead adherent of Magón's core ideology. To refer to Magonismo without this distinction would not be dissimilar from speaking about a party: 'I am Magonista, I am from the PRI [Partido Revolucionario Institucional], I am Obradorista'.

That is already returning to the confines of understanding politics through the party-form, and I am not interested in such a thing. Magón did not support this, so I think that if you talk about Magón, or if you really believe in the Magonista conception of anarchy, in all its forms, then you have to investigate well, separately, and concur with those notions".

A memorial without history, a memorial without community

On January 3, during his morning conference, president López Obrador announced that this year would be devoted to commemorating Ricardo Flores Magón.

"Have you seen statues of Ricardo Flores Magón? Nothing, nothing. Precursor of the Revolution. Because the ruling classes didn't like him, that's why he was always in jail; but he is an extraordinary figure in our history," said the president.

Since that day, the image of the Oaxacan anarchist appears every morning in the national palace. However, for Carrizo, this official image of Magón seems to be far from what he would have wanted.

"When president Obrador appointed 2022 as Ricardo Flores Magón's year, the idea seemed so far-fetched. This choices is only for people who have no understanding of Magón's history, his life and work " says Carrizo.

"Regardless, knowing why Magón died, what he was fighting against – his ideals and principles are fundamental."

As an example, he brings up a story that his grandfather, Maximiliano, told him. It is the story of when Teodoro, Ricardo's father, arrived in Eloxochitlán.

Carrizo tells that Teodoro was an enlightened man from the municipality of Mazatlán, near Teotitlán, Oaxaca. The man was well known in the Mazateca highlands.

"Teodoro was known here as the 'tata', the person who knew, the one who the people asked for guidance through his advice; and he gave them advice if there was a land issue, or a family problem, because he was a person who knew how to read and had worked on acquiring a particular kind of useful knowledge."

This fact, Carrizo narrates, made that when the war broke out due to the French intervention, in 1862, a liberal captain named José Ignacio Figueroa invited him to fight against the French in Puebla. Teodoro agreed.

"Teodoro visited all the towns. Among them, he arrived to San Antonio (Eloxochitlán) and collected three hundred Mazatecos. They went to Puebla. Finally when they arrived there, the people got to know each other, from all over the sierra, and they became friends; but when they returned from there, I saw the people of this town remained the same, as in all the towns.

There was no intellectual growth, people did not know how to read: there were only two or three people who could. And it was very interesting for the friends who had been with Teodoro in the war, to ponder: why couldn't the people read?" inquired Carrizo.

That's when Teodoro Flores and his wife Margarita Magón decided to settle in San Antonio Eloxochitlán:

"They taught people to read.

Although they had realized Teodoro’s literacy, he nevertheless was not a teacher, he was merely a person who knew how to retrieve this knowledge. It was Teodoro and Margarita's project to teach people to read so that they could get out of the darkness, get out of that chain where we are tied to, the cavern. That is how they arrived here, and it so happens that at that time they already brought their son, Jesús, who was born in Mazatlán [in the Mazateca mountains], in 1872 or 71, I don't remember well. But when they arrived here Ricardo was born: Jesús, Ricardo, and their parents.”

Ricardo, Jesús, and his parents were in Eloxochitlán for some time. The community, says Carrizo, loved them very much.

He even laughs and says that maybe Margarita brought the mole recipe to the town.

"Teodoro was not only an instructor who taught the folks to read, but he knew many things, he knew about trades and crafts. He knew carpentry, he taught how to plow the land too, because there was no such thing here, he taught how to plant vegetables, how to plant corn well, many things. His wife, they say, because she was from Puebla, was the one who taught him how to make mole stew".

Sometime later the couple decided to move with their children to Teotitlán. There, Ricardo went to school. He later moved to Mexico City, where he would study at the National School of Jurisprudence.

"Teodoro was a libertarian, and he was a liberal, a colored liberal. They had a plan, a project for the children: to learn to read, write, and study something to defend our territory later, to defend and fight for the poor people," Carrizo emphasizes. And so they did.

However, for Carrizo, the legacy of Ricardo Flores Magón has been hijacked by his natural enemies: the rich and the powerful.

"In the community, currently, there are people unaware of this fundamental notion, who don't know how to read, and they don't know Magón's history. For them, the Flores Magón family means nothing. The year of Magón's assassination means nothing to them because they don't know the relevance of their own history" he reflects.

He adds:

"People say, 'I am Magonista', in order to gain some advantage over others, to gain privilege in the community. They fly the Magonista flag to exploit the strength of the community. That has happened in many towns, not only here. That is what is worrisome. The community believes in this, because the community does not know the entire context. As I say, if we knew the history of Magón, we would know what capital is, what communism is. If we regained all that knowledge communally, another rooster would sing for us".

Apothecary Magonistas

Upon entering Eloxochitlán, a statue of Ricardo Flores Magón welcomes visitors. In one hand he carries a Regeneración newspaper while the other is held high, with a clenched fist.

His presence is pivotal for the events unfolded in a town that, although partly unaware of its history, partly recalls some of Ricardo's legacy. For a long time, Carrizo says, Magón's legacy in his town has been distorted by politicians and caciques. One example of this is the destruction of the communal assembly, the highest organ of self-determination and autonomous governing in the town. Originally inseparable from the social fabric, upon the distinction brought by the State to create a new sphere — that of ‘representatives’ and bourgeois tenets of ‘civil society’ — the assembly became a space contested by political parties.

Ricardo's symbol has, unfortunately, been present in these events.

"There are many who take advantage of this connection, and call themselves Magonistas. Many of us have realized that they take advantage of that flag to deceive others. Here, what we want is the solidarity through intellectual but also sensorial questions. We know it is essential to get to know people. To talk to people. To give something, expecting nothing in return. But the politicians who say 'I am a Magonista', here, they are asking for support from the government, and that support is used to deceive and rule over others. This system of intellectual repression, repression of thoughts".

Work and mutual support, essential in the practice of Magonismo

The talk goes on without us realizing it and we manage to address some details of Magón's practice that stand out more to Carrizo, who with his example has tried to show that it is possible to live well without following the tendencies of extreme individualistic capitalism:

"I can plant my cornfield to eat, to survive a little. And people do it here, Magón said it well: here it is. I can plant my coffee, to have coffee, I can raise my animals, but in the case of solidarity, of mutual work, I help here and they help me too, we help each other, right? This is the essence of the traditional, ancestral practice that has existed since time immemorial.

However, although people still help each other, these forms of cooperation have been eroded, to a large extent, by the overwhelming presence of money, as Carrizo says,

"if you don't have money you are nobody, that's how people react at this point. She who has money is the one who commands, she is the one who accomplishes most things; but before money was not used, in previous eras they did not use currency, it was either exchange through trade, or there was mutual aid, cooperation. In here there was a lot of that".

"If there were a hundred people in the community, well, a hundred people participated in your planting, and in two or three days all that was done.

The people produced a lot. They built the houses quickly: some would bring wood, others firewood. Everyone contributed.

The food was the same, everyone provided grains, beans, sugar to sweeten our coffee, and things like that. Together all helped each other, that form of socializing was commonplace.

When the bombardment of capitalism arrived, everything ended. It ended little by little, and now we are submerged by all of this", the artist from Eloxochitlán relates vivaciously.

His criticism is tenacious as he points out that "this world is no longer the world we dreamed of, the one Magón dreamed of. The world Magón dreamed of was a world of harmony in which everyone would be on the same level. There should not be two classes, only one category of human beings, nothing more".

Political parties and the figure of Magón

Carrizo insists on the contradiction between Magón's thought and the figure of Ricardo Flores Magón himself, constantly used by politicians, bureaucrats, and individuals who disregard libertarian practices and, if aware, they scorn them to impose the rule of money.

A glass of water in hand and holding the guitar with the other, Carrizo Trueno continues: "

Magón does not need celebrations, a flag or a crown to be raised for him. No. You have to practice his visions, you have to put them into practice. I think like this: you have to do things, not be saying that I am a Magonista, or wear insignias of Magón, no, that should not exist. People with money, powerful people, they do that. They are always looking for the limelight so that they can be seen on television as Magonistas.

"Everything becomes a contradiction when it comes to repression. When, if there is no reason, why? Why are people, and communities, being apprehended? The government is responsible for this situation because there have already been many protests, it is time for the people who are there to be released," Carrizo answered forcefully when asked about this propagandistic use of Magón, in this case by the president himself and the existence of seven political prisoners originally from Eloxochitlán.

Carrizo shared with us some ideas on how the figure of the anarchist could be better preserved.

"Do not forget to practice his tenets, to put his ideas into practice.

To respect each other, to focus our minds and ideas on conserving our planet, conserving our environment, and honoring each other. I invite people not to surrender, to be analytic, critical, and to delve into this history of Magón, to delve into the culture, because by knowing our culture, we will be a living population, by knowing our culture, a population that does not have a living culture is a population that does not exist, it is a dead population. So, we have to keep a lot in mind: through understanding our history, and how and why the events unfolded, we will be liberated".

Before leaving his house, he invites us to some cups of coffee and some of the traditional bread. He shows us his kitchen and gives us some of his drawings, where characters of the Mazatec cosmovision appear. We shake his hand tightly before saying goodbye.

Alejandro Ruiz

Independent journalist based in the city of Querétaro. Alejandro believes in stories that open spaces for reflection, discussion and collective construction, with the conviction that other worlds are possible if we build them from below.

Heriberto Paredes

Photographer and independent journalist based in Mexico with connections in Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Costa Rica, Cuba, Brazil, Haiti and the United States and a member of taller ahuehuete.

Ruiz, Alejandro. Paredes, Heriberto. “Magonista es una palabra nada más”, June 18th, 2022. Translated by taller ahuehuete in solidarity from the original version initially published by Pie de Página.

an old man; a little old man; or, a character in a comical traditional "old men’s" dance. Orthographic Variants: huēhuēntōn, uehuento, huehuento

Regeneración was a prominent anarchist newspaper that functioned as the official organ of the Mexican Liberal Party. Founded by the Flores Magón brothers in 1900, it was forced to move to the United States in 1905 due to censorship and persecution. As described by José Revueltas, “Flores Magón understood that the struggle for the pure reestablishment of democratic freedoms (the validity of the Constitution of 1857) was not the proletarian demand that the working class should demand from the revolution and that in order not to continue "being as slaves as today", the workers should fight, together with political freedom, for "economic freedom".

Mazate: a variety of deer, whose scientific name is Mazama americana, of the family Cervidae. It is smaller than the common deer or white-tailed.