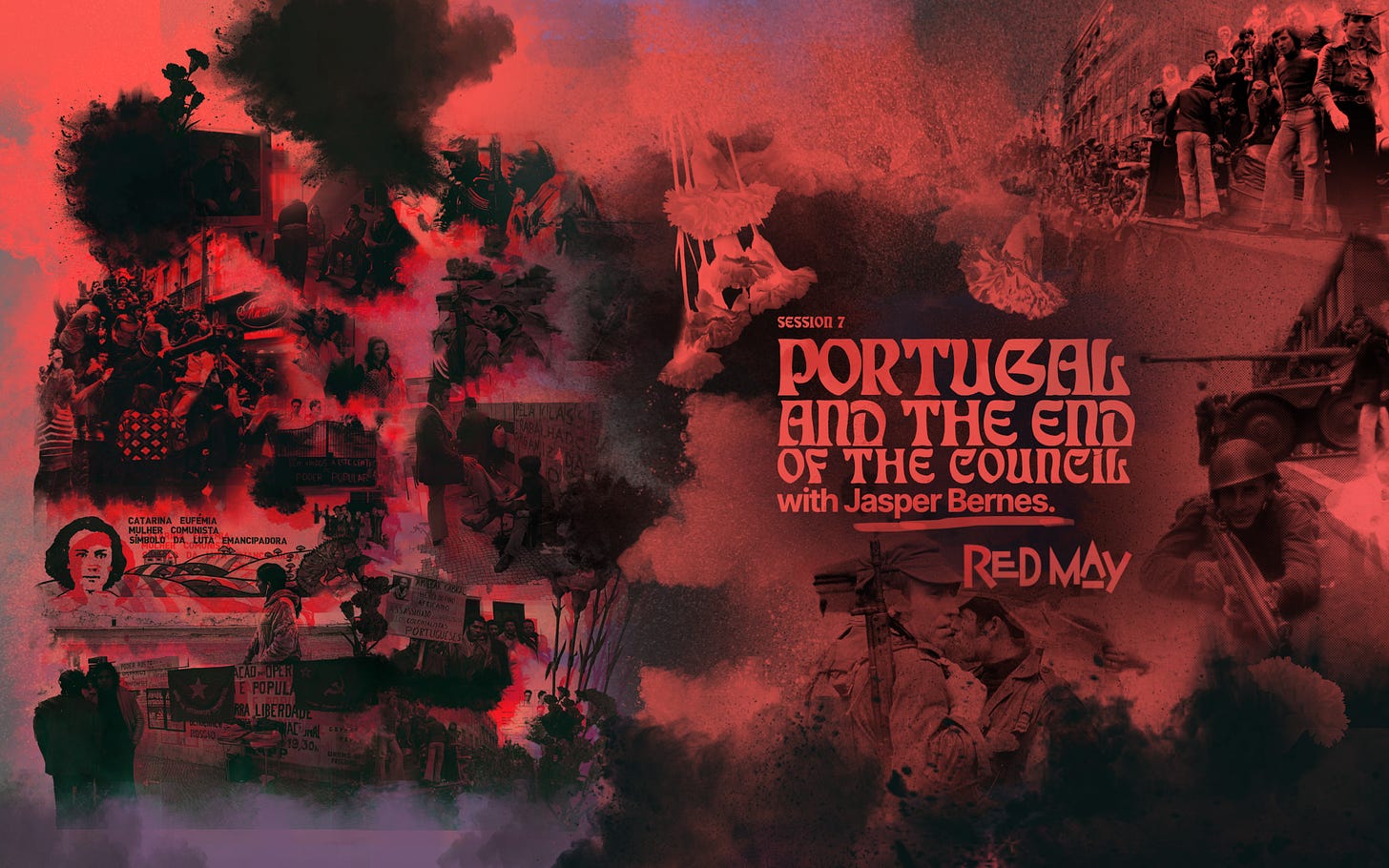

Portugal and the End of the Council

In Portugal, a unique dynamic came into play which would in fact come to characterize the coming era as such and to foreclose any emancipatory associations for the notion of workers’ self-management.

Section 7 – April 2, 12 pm PST

Portugal and the End of the Council

Hosted by Jasper Bernes and Red May

✎ Reading time: 4 minutes.

Excerpt by Jasper Bernes

The Portuguese Revolution casts all of the characters introduced so far —council, mass strike, red army, party, fascism, and antifascism, etc.— and writes an ending for the workers’ council around them. We might have chosen Chile, Poland, or Iran. In all of these instances, workers’ councils, or something like them, form very broadly, throughout a part of the industrial base. But in none of them do the councils project or move toward a break with capitalist reproduction — on the contrary, inasmuch as self-management or autonomy is projected by these councils it is an autonomy oriented toward integration. The radicality of autonomy increasingly becomes a radicality of form that accepts and even affects a reformist content. Nonetheless, we cannot blame communists for seeing in these councils a communist potential, for that is what the era could now of the 1917-23 sequence.

The Portuguese Revolution confirmed the suppositions of soixante-huitard council communists that a new era of councils arrived, and yet it provided a situation in which those councils were by their nature not only inadequate to the task at hand but forced to work at cross-purposes and undermine the construction of council power. Even if they had armed themselves and forestalled the counter-revolution of the movement of the nine, they would have had to confront the fact that the councils which had fallen under self-management were dependent upon the state as it existed and capitalism.

In Portugal, a unique dynamic came into play which would in fact come to characterize the coming era as such and to foreclose any emancipatory associations for the notion of workers’ self-management. Significant here was the fact that council power did not emerge in one fell swoop, and because there was limited union penetration, not all workplaces had councils. But the Portuguese industry in the south was concentrated, centralized, and also small, and so many of the most important sectors of the economy were formed as a council. These were conglomerates that were essentially dependent on the state.

The firms that fell into self-management, where once the owners and managers had fled, were often barely sustainable economically without hyper-exploitation and state subsidy.

Trying to manage them in a way that had higher wages and better conditions not only meant they had to produce things differently but in many cases meant they needed to produce entirely different things. The firms which passed into self-management were often the least productive enterprises, which would be undersold in open competition with other producers, and so needed to either work hard or be protected from the markets. They could appeal to the state for credit or to the movements for solidarity.

Unless markets and money were abolished and something else put in their place capitalist restoration was assured, but within Portugal, this was never a real demand. Instead, the demand was for autonomy for the workers’ councils, but one expressed through their demand for improved conditions. On such a basis the reimposition of capitalism was certain. Only a wholesale reorganization of the structure of Portuguese industry, not to say the division between industry and agriculture in the industrialized south, where large commercial tracts abounded, and small farmers in the conservative, unproductive, Catholic, and increasingly pro-fascist north, nor the boundaries between Portugal and the Spanish economy, itself convulsed by a wave of struggles that would end the Franco regime.

As a structure, the workers' committees could not become the basis for such an effort and indeed the PRP-BR and LUAR often focused their centralizing energies elsewhere, in the neighborhood assemblies and housing occupations and other place-based bodies which were in fact more reliably committed to the project of autonomy and working alongside the COPCON. Even though this was arguably one of the purest expressions of councilar near-revolution, the locus of action was no longer in the workplace. Something had changed, but it would take decades to recognize what.

Join us for Section 7, April 2, 12 pm PST.

Reading material:

Charles Reeve et. al, Portugal: Anti-Fascism or Anti-Capitalism, Root & Branch

Mailer, Phil. Portugal, the Impossible Revolution? Black Rose Books ; F32. London: Solidarity, 1977.

Loren Goldner, “Class Struggle and the Modernization of Capital in Portugal, 1974-5”

More files here.

Catch up, or rewatch previous sessions:

Access the PDFs here.