“The Treason of the Artist: Alyosha Karamazov and the Rejection of the Hermit’s Exodus from Omelas”

A Critique of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Dystopian Tale

“Rebellion? I wish you hadn’t used that word,” Ivan said feelingly. “I don’t believe it’s possible to live in rebellion, and I want to live! Tell me yourself – I challenge you: let’s assume that you were called upon to build the edifice of human destiny so that men would finally be happy and would find peace and tranquility.

If you knew that, in order to attain this, you would have to torture just one single creature, let’s say the little girl…would you agree to do it? Tell me and don’t lie!”

“No, I would not,” Alyosha said softly.

After the inevitable comparisons between the present excerpt and her 1975 short story, in her essay “The Scapegoat in Omelas'' Ursula K. Le Guin clarified:

"The central idea of this psychomyth, the scapegoat, turns up in Dostoevsky's Brothers Karamazov, and several people have asked me, rather suspiciously, why I gave the credit to William James. The fact is, I haven't been able to re-read Dostoyevsky, much as I loved him, since I was twenty-five, and I'd simply forgotten he used the idea." Later she added, when alluding to Dostoevsky's ideological switch, that the once-Siberian political prisoner had shown "early social radicalism," yet became “a violent reactionary."

Le Guin’s appraisal of Dostoevsky’s trajectory prevented her from engaging with his oeuvre openly: the full immersion into the inner thoughts shared by the philosophical novel's protagonists was hindered by the reductive discernment of the author’s political alignment, which she found disappointing despite the contextually peculiar circumstances.

Dostoevsky’s meditations and thought-trajectory after prison did not oppose what one could adventurously describe as a newly acquired Hegelian-Marxist root, as it has been labeled recently – albeit dogmatic, Christian Orthodox, and drenched with immaterial materialism. The transmutation of his creed remained a hazy, idealist faith in humanity. In his essay "Socialism and Christianity", whilst incomplete, Dostoevsky stated that civilization had “become degraded, embracing liberalism and laity.”

In the book "The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia," K. Lantz describes how the Russian novelist "asserted that the traditional concept of Christianity should be recovered.” He thought that Western Europe had ‘rejected the single formula for their salvation that came from God and was proclaimed through revelation, 'Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself', and replaced it with practical conclusions such as, 'Chacun pour soi et Dieu pour tous' [Every man for himself and God for all], or "scientific" slogans like 'the struggle for survival'."

Dostoevsky did not, however, bother identifying his new position openly, never projecting any categorical nomenclatures outside the label of an all-encompassing social Christianity. His early radicalism was transmuted after his prison insights –through his compulsive reading of the Christian gospels– towards a credence-rooted concern with the meaning of ethical delineations applied to individual and communal living. Consumed by the complexity mediating social relations, the novelist aimed to document the way ethical questions intercepted the subject by placing the entire weight of a potential life choice (“to steal or not to steal, to kill or not to kill”) on the individual’s decision to act rather than on the conjunction of simultaneously limiting forces gravitating systemically, impelling the human in question to see her options reduced to what under the lens of liberalism we would read as “evil” or assign as “good”. Jean Valjean steals a loaf of bread to feed his widowed sister and her seven children, but why are the ethical implications solely surrounding this specific act, while the system that allowed starvation is absolved, or worse, not even contemplated in the equation?

Dostoevsky’s stance –found in his almost-compulsion with these recurring themes– remained quietly in the background despite the rejected political taxonomy. It was this same obsession (and his "preoccupation with the destitute and the disadvantaged") the parallel that drew him initially to utopian socialism in his youth, and the same drive that informed all his literary endeavors after his release from prison.

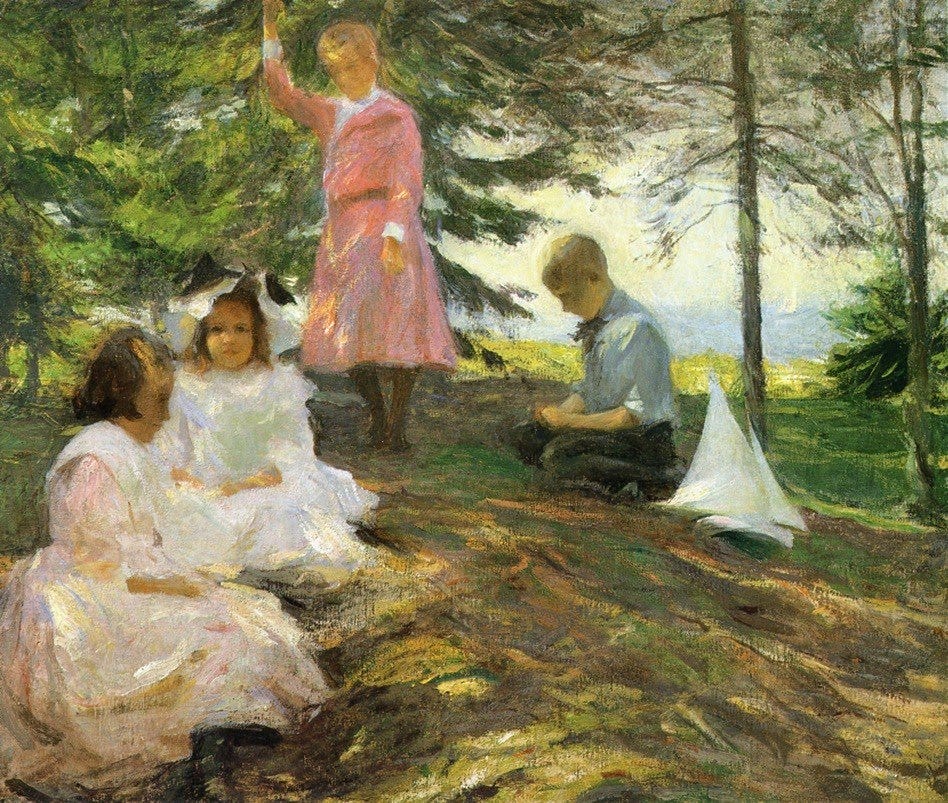

But what informed Le Guin’s worldmaking, as the creative architect of Omelas? The canvas of her utopia reflects from inception a midsummer-esque, pagan vignette. As if zooming from within a genre painting, the turbulent, eventful representation of crowds, floral arrangements, and horse racing (amongst other ludic activities) positioned the reader in a variant of a prototypical Scandinavian summer day. Le Guin narrates that the residents of Omelas “were not simple folk, you see, though they were happy.” We understand their happiness through their outdoor activities and their sunshine-soaked afternoon. She proceeds, matter-of-factly:

“They did not use swords, or keep slaves. They were not barbarians. I do not know the rules and laws of their society, but I suspect that they were singularly few. As they did without monarchy and slavery.”

But this was a deceptive portrayal, as we soon find out, for the inhabitants of Omelas relied on the existence of a starved and imprisoned child to maintain their festive hedonism, their joyous modus vivendi.

Through a dizzying, almost camera-panning of the scenery, the author sketches a landscape that varies vastly from the desert horizon I recognize as my hometown. I am, from its genesis, an outsider to this foreign land. Surrounded by the ornamented greenery of the tale, one can’t help but wonder: is the spell of Omelas specific to this region, or could a similar social contract take place in less greener grounds? How would that work? Would the Sahara be, for example, fully replenished with newly-appeared oases? Could Omelas be instituted on a geography that lacked "moss-grown gardens” and “avenues of trees, past great parks" and a "great water-meadow"? Could Omelas take place, for instance, in the Great Sand Sea if such accord between the populace was reached? The capability of Omelas’ spell (found in the consensus of the “child-captivity-turns-land-prosperous” equation) remained rather unclear throughout the tale.

By the request of expecting us, the audience, to fill in the blanks with our preferences in this utopia-making collective exercise, Le Guin asks us to partake in the creation of Omelas.

“Perhaps it would be best if you imagined it as your own fancy bids, assuming it will rise to the occasion, for certainly I cannot suit you all.”

Her utopian society is unfinished and undefined, still in progress, yet we are expected to believe in its irrevocable substantiality.

Omelas is described through omission. The organizational structure is unknown at first. The author opted for the creation of this unique dreamland by emphasizing embellishment and detail, skipping the scaffolding, and going directly for decor and ornamentation. Omelas was implausible and introduced by an unreliable narrator. The fundamental aspects of this civilization were still open for negotiation.

The invested efforts into the creation of Omelas pale in comparison with the vast accumulation of details dedicated to the narration of the precarious and inhumane conditions taking place inside the basement where the imprisoned child was kept ransom by the community. While Omelas is a DIY and vague utopia, the suffering existing inside the dark and horrific prison cell is on the other hand palpable, soaked with tangibility: the horror is powerfully communicated, full of atmospheric despair, enraging and meticulously specific.

Paradoxically, Le Guin mentions:

“The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by pedants and sophisticates, of considering happiness as something rather stupid. Only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting. This is the treason of the artist: a refusal to admit the banality of evil and the terrible boredom of pain [...] if it hurts, repeat it. But to praise despair is to condemn delight, to embrace violence is to lose hold of everything else. We have almost lost hold; we can no longer describe a happy man, nor make any celebration of joy.”

Strangely, the treason of the artist she describes is committed by the author herself.

Despite the association she claims surrounds the pedantic and sophistic tendency that compels artists to engage with pain as a subject matter worth exploring, her abundant descriptions of this same “boring” and “banal” pain experienced by the prisoner contain the pellucidity her arcadia lacks. If “it hurt”, Le Guin was perhaps unaware but eager to “repeat it” to us, her readership.

The joy attributed to Omelas was such that the author, disinterested after outlining the general gist of a carnivalesque scene, advocated for our participation quickly, unable to continue the narration alone. The reader is complicit in the writing of an exquisite-corpse that intends to be a conceivable communal utopia. Nevertheless, the improvised sentences of this cadavre exquis project proclaim the depth of a Dostoevskyan novel.

As if a result of a self-fulfilling prophecy, the author proved that one “can no longer describe a happy man,” at least for not too long. Her first paragraphs, the literary foundation of Omelas, indirectly condemned delight by the lack of commitment to a coalesced, concrete, utopian society. Her first scenes considered happiness indeed as “something rather stupid”, impersonal and not concise, not worth exploring meticulously. Despair, however, and the embrace of violence overcame the celebration of joy in the tale as soon as it was established in the climax.

For Walter Benjamin, the celebration of joy Le Guin advocated for was the wish image, the clamors of despair from the masses facing the not-yet realized communal happiness:

“Corresponding to the form of the new means of production, which in the beginning is still ruled by the old (Marx) are images in the collective consciousness in which the old and the new interpenetrate.

These images are wish images; in them the collective seeks both to overcome and to transfigure the immaturity of the social product and the inadequacies in the social organization of production.

At the same time, what emerges in these wish images is the resolute effort to distance oneself from all that is antiquated – which includes, however, the recent past. These tendencies deflect the imagination (which is given impetus by the new) back upon the primal past.”

The statement: "only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting. This is the treason of the artist: a refusal to admit the banality of evil and the terrible boredom of pain” stands out on its own due to its unequivocal, absolutist tonality. Perhaps it could apply to Omelas as a fiction piece, where what hurt was extended, intellectualized, and repeated ad nauseam. The horror of the tale is what most recall after reaching the ending.

The residents of Omelas are joyous. This is reiterated often:

“How to describe the citizens of Omelas? They were not simple folk, you see, though they were happy. And old women, small, fat, and laughing, is passing out flowers from a basket..."

This alluded laughter, and the described "boundless and generous contentment, a magnanimous triumph felt not against some outer enemy but in communion with the finest and fairest in the souls of all men everywhere and the splendor of the world’s summer: this is what swells the hearts of the people of Omelas, and the victory they celebrate is that of life" is remarkably similar to the one described by Theodor Adorno in his 1944 essay:

“Fun is a medicinal bath. The pleasure industry never fails to prescribe it. It makes laughter the instrument of the fraud practised on happiness. Moments of happiness are without laughter; only operettas and films portray sex to the accompaniment of resounding laughter [...] In the false society laughter is a disease which has attacked happiness and is drawing it into its worthless totality.

To laugh at something is always to deride it, and the life which, according to Bergson, in laughter breaks through the barrier, is actually an invading barbaric life, self-assertion prepared to parade its liberation from any scruple when the social occasion arises.

Such a laughing audience is a parody of humanity. Its members are monads, all dedicated to the pleasure of being ready for anything at the expense of everyone else. Their harmony is a caricature of solidarity.”

Omelas’ joyful scene reads indeed as a caricature of solidarity, a mockery of communal spirit. Was Adorno not acutely close to describing Le Guin’s wish image, when pointing out (unbeknownst to the German philosopher) how the “laughing audience is a parody of humanity”? The citizens of Omelas wouldn’t be far from “monads, all dedicated to the pleasure of being ready for anything at the expense of everyone else. Their harmony is a caricature of solidarity.” Le Guin reiterates: “They were not naive and happy children— though their children were, in fact, happy. They were mature, intelligent, passionate adults whose lives were not wretched.” Yet this harmony was obtained through the captivity and torture of a human child, making their harmony a caricature of solidarity, a parody of the utopian commune.

Adorno's attitude post-1940 regarding his hope for social change has been rightfully described as pessimistic. To Le Guin, he must have been complicit in the treason aforementioned. Theodor W. Adorno, after all, stated in his formidable essay Commitment (1962):

“I do not want to soften my statement that it is barbaric to continue to write poetry after Auschwitz. . . . The abundance of real suffering permits no forgetting; Pascal’s theological ‘On ne doit plus dormir’ [‘Sleeping is no longer permitted’] should be secularized. But that suffering—what Hegel called the awareness of affliction—also demands the continued existence of the very art it forbids; hardly anywhere else does suffering still find its own voice, a consolation that does not immediately betray it.”

The treason of the artist predisposes one's creative preference (a choice!): the boredom of pain over the refusal to delve into delight and joy. Nonetheless, this claim assumes that this is a conscious judgement, as if freedom of thematic content existed because joy was equally distributed and experienced amidst those relegated to the corners of society, unable to participate or make a professional career out of their craft like Le Guin herself. Despite this, and using as a resource what Hegel referred to as “the awareness of affliction,” these treacherous artists (or, if following the capitalist mode of production’s distinction: these artisans, as well) still write, still create. They might accomplish this treacherously, to Le Guin’s horror, following simply a desperate aim to express their suffering. But there is joy in the victory of creation: it’s the triumph of work when not attached to the oppressive chains of our known alienated labor, when independent of a drive for profit.

The Irish-Mexican philosopher John Holloway described this as the “doing through non-identity”, the refusal-through-creation. It can only be obtained through pairing our sincere acknowledgment of the perils surrounding us, but creating nevertheless:

“Non-identity can only be a force that changes itself, that drives beyond itself, that creates and creates itself. And where do we find a creative and self-creative force? Not animals, not god, not nature, only humans, we. Not an identitarian we, but a disjointed, misfitting, creative we.”

What is the state of the art in Omelas, then? The author described that:

"They know that if the wretched one were not there sniveling in the dark, the other one, the flute-player, could make no joyful music as the young riders line up in their beauty for the race in the sunlight of the first morning of summer."

Is the flute player not committing a larger treacherous act for, as an artist, he prefers the composition of a joyful tune (he is in fact described with his eyes closed, perhaps to reality as well) rather than the mimetic depiction of the oppressive regime that allows his playing, of which he is complicit? Aware of the subjugation supposedly required to continue playing, the musician opts instead to continue his happy melody.

The art in Omelas is not autonomous, following this admission:

"They know that they, like the child, are not free. They know compassion. It is the existence of the child, and their knowledge of its existence, that makes possible the nobility of their architecture, the poignancy of their music, the profundity of their science."

The “profundity” ascribed to Omelas’ scientific discoveries is never explained, but one can argue that, if so was the case, technological advancement would’ve discontinued the (so-called) necessity of a child’s enslavement.

Theodor Adorno, in regards to Le Guin's portrayal, would categorize the "nobility of their architecture, the poignancy of their music" as 'light art', for:

“Light” art as such, distraction, is not a decadent form. Anyone who complains that it is a betrayal of the ideal of pure expression is under an illusion about society. The purity of bourgeois art, which hypostasised itself as a world of freedom in contrast to what was happening in the material world, was from the beginning bought with the exclusion of the lower classes – with whose cause, the real universality, art keeps faith precisely by its freedom from the ends of the false universality.

Serious art has been withheld from those for whom the hardship and oppression of life make a mockery of seriousness, and who must be glad if they can use time not spent at the production line just to keep going.

Light art has been the shadow of autonomous art. It is the social bad conscience of serious art. The truth which the latter necessarily lacked because of its social premises gives the other the semblance of legitimacy. The division itself is the truth: it does at least express the negativity of the culture which the different spheres constitute.

Omelas’ concept of artistic treason contrasts with English author and painter John Berger's perspective, and his decoding of the power of the word.

For Berger, and in accordance with the concurrent position shared by many marginalized groups in search for autonomy through creation (a similar position is held, for example, in the Zapatista movement), one explores and feels impelled to create by this "refusal to admit the banality of evil and the terrible boredom of pain" because:

"Poems, even when narrative, do not resemble stories. All stories are about battles, of one kind or another, which end in victory or defeat. Everything moves towards the end, when the outcome will be known. Poems, regardless of any outcome, cross the battlefields, tending the wounded, listening to the wild monologues of the triumphant or the fearful. They bring a kind of peace. Not by anaesthesia or easy reassurance, but by recognition and the promise that what has been experienced cannot disappear as if it had never been. Yet the promise is not of a monument. (Who, still on a battlefield, wants monuments?) The promise is that language has acknowledged, has given shelter, to the experience which demanded, which cried out.”

For Berger, the construction of an artistic space where the state of pain is acknowledged is not with a sophistic or pedantic purpose, but to provide solace and recognition to the sufferers of a world that keeps moving on without justice. This world brings a renewed sunrise every morning, replacing a newspaper headline with a different catastrophe. It is silent when the sufferers beg our solidarity in the face of human pain, war, injustice, and exploitation.

Following a similar train of thought in his 1976 essay, Eduardo Galeano stated:

"[T]he act of creation is an act of solidarity which does not always fulfill its destiny during the lifetime of its creator."

Begging to cease an "intellectualization of pain" is difficult while functioning outside the boundaries of the alienated privilege granted to a few by the ruling class. As the rest of the world’s population drowns every day in an attempt to seek refuge from an incessant deluge of injustice and subjugation, to write about the tedium of pain isn't aiming to "praise despair,” and therefore “condemn delight." We cannot condemn delight, for we have collectively encountered it so briefly, so fleetingly – simply acquainted to it as an exception to the rule, a crack in the system. So we revisit and draw from what we know, limited by the structures reflected in our societies until we sublimate this deterrent by deterritorializing and critiquing immanently what is assumed to be, what is expected to stay the same. We create, ultimately, by merely transforming nature. It is the individual, her society, and her means of figuration which have constituted the pillars of creation throughout human history.

Part of the efforts surrounding revolutionary autonomous Latin-American literature (a practice shared not exclusively to these circles, however) involves the act of embracing both simultaneous realities – art not only as a mirror to society, but a window. As there is pain, there is joy. The exclusive exhaustion of one individual theme is the rejection of the other.

The Uruguayan author Eduardo Galeano intended, through his writing, to:

“understand how richness and poverty are intimately connected, and also freedom and slavery are intimately connected. And so, there are no richness really innocent of any poverty […] to interlink histories that have been before told separately and in this codified language of historians or economists or sociologists.”

Dostoevsky, Berger and the “other arts,” the “unheard” voices always balance these two notions, hence providing entrance into our concrete reality, mirroring its complexity without shying away. They hope to embrace rather than to divorce, the latter being the Western tradition’s methodology through its reverence of hyperspecialization and reification of thematic content.

Galeano added in his 1988 essay "In Defense of the Word”, as if responding to Le Guin’s accusation of treason that:

"One writes against one's solitude and against the solitude of others [...] One writes, in reality, for the people whose luck or misfortune one identifies. [...] How can those of us who want to work for a literature that helps to make audible the voice of the voiceless function in the context of this reality?

Just as Das Kapital is not an intricate description of a utopian society, but a mere critique of the insidious complexity of capitalism (with its value-form shackles, and its branches of hell), the same conundrum applies to writing about perfect societal harmony under our paradigm. It is a truly complex task that cannot manifest itself through denial. It requires closing our eyes, clenching our teeth and ignoring-while-addressing the global injustices endlessly developing. It requires behaving like the architect who raises her structure in imagination before she erects it in reality. And just as Marx understood this, Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés addressed this particular issue in his 2016 communiqué, "The Art that is Neither Seen Nor Heard":

"To even make something tiny that will contribute to the new world requires that we involve ourselves profoundly in the science and art of imagination, in the gaze, in listening and in creativity, patience, and attention.

Much has been written –particularly in the past century– about the position of aesthetics and politics, their interlinking, and their symbiotic existence. But regarding Ursula's "treason of the artist," that is, our inability to describe what is not painful but rather be fixated on the opposite, Galeano added:

"In this respect a "revolutionary" literature written for the convinced is just as much an abandonment as is a conservative literature devoted to the… contemplation of one's own navel.

In Latin America a literature is taking shape and acquiring strength, a literature... that does not propose to bury our dead, but to immortalize them; that refuses to stir the ashes but rather attempts to light the fire... perhaps it may help to preserve for the generations to come . . .”

It is not by the omission of the hopeful promise of utopia (which unravels every day in front of our eyes when tenderness and community are chosen over capital), but by the coexistence and artistic recreation of both suffering and hope that one is able to formulate a world that is tangible and accessible to all. After all, if given the chance, what would the imprisoned child’s retelling of his side of the story sound like?

The art that acknowledges the battlefields (the art that is neither seen nor heard as Subcomandante Moisés stated) is the type that would interest Alyosha Karamazov the most – a character Le Guin dismissed in her rejection of Dostoevsky.

The hedonistic nature of the characters in Omelas is not dissimilar to that of the patriarch Fyodor Karamazov, yet Dostoevsky fleshed out this dramatis persona while the citizens of Omelas remained in the distance, soaking in the sunshine. No character development or depth in Omelas takes place except for minor inner conflicts germinating from within a few of its inhabitants. We hear about such conflict through the aerial view following the heroic dissidents who, unable to carry the weight of guilt, independently walked away from Omelas, independently walked away from the enslaved child.

Although the product of a reactionary man, Dostoevsky’s character Ivan Karamazov discusses the same subject, the same child materialized as Omelas’ prosperity-transaction. Ivan describes the infant, nevertheless, with humanity and dignity while Le Guin herself removed all integrity from the victim-figure, addressing the child in fact with the pronoun it. She mentions:

“In the room a child is sitting. It could be a boy or a girl. It looks about six, but actually is nearly ten. It is feeble-minded. Perhaps it was born defective or perhaps it has become imbecile through fear, malnutrition, and neglect. It picks its nose and occasionally fumbles vaguely with its toes or genitals, as it sits haunched in the corner farthest from the bucket and the two mops. It is afraid of the mops. It finds them horrible.”

Ivan Karamazov –who presented the concept to LeGuin initially– speaks of the child with protective terror, not with grotesque distance and uncertainty. Ivan, terrifying as he was, abstained from objectifying the child-prisoner in the paradoxical ethical dilemma while offering it with terror to his pious brother.

He wasn’t a saint. The provocateur Ivan Karamazov was sharp, well-read, intellectually perceptive, and disturbed. Under a superficial appraisal the middle child of Fyodor Pavlovich functioned as an avatar for the individualistic, secularized approach to thought hegemonically upheld in the Age of the Enlightenment.

In an earnest depiction of the damage the XVII and XVIII European ideology permeated on young men of intellectual proclivity, Dostoevsky dissected how the sovereign pursuit of Reason exacerbated the separation between human and community. This conflict was painted frequently, with his novels always juxtaposing two positions: the supreme rationalism of the progressive urbanite versus the conviction of the untutored, provincial, naive yet intuitive communal stance often reliant on esoterism.

While engaging with the dialogue between Alyosha Fyodorovich and his older brother, it is easy to forget at times that these were two siblings arguing their filial predicament, as one cannot overlook the ‘progressivism’ permeating individual liberty in Ivan versus Alyosha’s mystical (almost phantasmagoric) desire to define himself and the world through social relations, through unfeigned interconnection with others. Of the youngest brother Karamazov it is said:

“...In his heart there is the secret of renewal for all, the power that will finally establish the truth on earth, and all will be holy and will love one another, and there will be neither rich nor poor, neither exalted nor humiliated.”

Although timid, the youngest Karamazov was not prone to conceal his stance, often controversial, always challenging the accepted social norms through his militant unmilitancy. Despite ultimately a pacifist figure, the aspiring Orthodox novice was not coy when expressing ideological disaccord as confronted by the eloquent, philosophically embedded speech-postulations of his interlocutors.

Alyosha Karamazov adhered to the central Orthodox dogma of theosis or theopoesis — the divinization of humanity. His solidarity with others is connected to this principle, not through the dismissal of evil but through the faith in individuals and their society. For Alyosha, it was through mitzvahs, deeds, dialectics, mutual aid and acts rather than intellectualized and abstractly postulated ethical or theological dilemmas that one could facilitate the arrival of the promised utopia.

But his brother Ivan was not a dogmatic rationalist, as the notion contradicts one another. Furthermore, Dostoevsky’s characters rarely ever suffer from unidimensionality. In an attempt to contradict the religious fervor of his brother Alyosha’s defense of a spiritual commune, the atheist Ivan interjects the same premise of the present short story we’ve examined. Yet, unlike the citizens of Omelas, Alyosha Karamazov did not hesitate, not even for a second. He declined the suggestion immediately, not even entertaining ponderation, as it impertinently contradicted his unorthodox philosophy and praxis.

Intellectual pursuits were not particularly enticing to him, except for the hermeneutics of the scripture. He favored identification with his fellow humans, empathy, and genuine understanding from those that surrounded him. He did not lack curiosity, his analytical mind was instead redirected to comprehending his surroundings. He lived, in other words, communally.

Alyosha saw participation, interaction, and discourse as a way to bring the kingdom of his messiah into the earth. He was not pastoral, but sincerely inquisitive. His rejection of individualism is prevalent throughout the novel. His disdain toward the bourgeois individual concept of spiritual flourishing allowed him to maintain insightful conversations with characters from all walks of life and ideological affinities, aware as he was that “the human essence is no abstraction inherent in each single individual. In its reality it is the ensemble of the social relations.” (Marx, 1844, 423.)

It is not preposterous to say then that, if given the chance, Alyosha Karamazov would not have walked away from Omelas. He would remain, organize collectively, and fight for the liberation of the enslaved child – fighting as well for true communization. This communal reality, at last concretely materialized, and as tangible as the “banality of evil and the terrible boredom of pain” we will experience every single day under capitalism until it is finally extirpated.

Fascinating. I find myself the appeal of Dostoyevsky is that of a man who faced the scaffold before exile. His work often alludes to an existential need to choose when faced with a binary decision. Like Camus or, controversially, Sartre when faced with joining the Resistance or collaborating with the Nazis. Omelas is no Utopia. It is more akin to Vichy - a comfortable compromise for many who knew what was being done to the Jews but were happy to participate in the crime. I'm for those who seek to engage and fight back. Omelas is real. It is pervasive. It is here and now.