La Extemporánea: from the liberation of the plantations to the Defiant Europe

Persevering and stubborn as they are in what they set out to do, the Zapatistas embarked on their journey to Europe. Subcomandante Moisés leads La Extemporánea, the EZLN's aircraft-borne delegation.

September 14, 2021

Text and photographs by Daliri Oropeza.

MEXICO CITY - Subcomandante Moisés raises both arms and the Zapatistas immediately pay attention. With his fingers pointing toward the sky, the gesture indicates the formation they must execute before entering the boarding lounge at the Mexico City International Airport.

Straightaway, the first team of the aircraft-borne delegation is placed in five rows, one behind the other. Taking advantage of a brief opportunity of stillness in the middle of the hectic airport, they advance together and enter the boarding lounges.

Moisés walks in front of what looks like a wise and colorful snake, one that knows how to move amidst the gray, dry atmosphere of the airport.

In silence and following an impeccable organizational method, the Zapatistas show proficiency when it comes to conducting themselves collectively.

They’ll arrive at dawn to Vienna, Austria, where they are heavily anticipated.

They remain calm, lined up in the dark corner of the F1 hall for international departures, holding their paperwork, passports in hand.

The purple caps of the Ixchel-Ramona Militia Section, a women's soccer team stand out, with their skirts and the occasional soccer ball they deflated to take to Europe. As no one is seen sporting their traditional red bandana, –an identifying sign of the conventional Zapatista attire– without that piece of cloth they seem [to the author] almost unrecognizable.

On stickers, embroidery, baseball caps, and even as a shield on their backpacks, the group sports the round crest of the Zapatista Air Forces (FAZ), which bears a flying beetle in the center, with a red bandana on its shoulders, similar to Don Durito de la Lacandona.

On the right white wing of the beetle is a red five-pointed star; on the left, the initials of the unit: FAZ. On the upper white ribbon, the motto in black letters, which summarizes the size of his bets and reads:

"Volantem est alio modo gradiendi"

(Another flight test)

Perplexed, the [non-indigenous] passengers look incredulously at the Zapatista delegation. The urge to document the scene overtakes them:

“What is this?”

“Where are they coming from?”

“What kind of delegation are they?”

Carrying large wheeled suitcases, the passengers are visibly impatient. A new line at the window of the Spanish airline is opened for those who have an early flight.

The delegation waited for two hours in formation in order to fulfill the bureaucratic process of checking-in, and proving their right to travel.

As members of the Indigenous National Congress chanted slogans, cheers, and songs of rebellion, the travelers stared without discretion at La Extemporánea and the participants of the emotionally charged sendoff.

The youngest – members of the Comando Palomitas – carry the FAZ crest on their shirts or blouses.

They are armed with simple snap cameras that resemble toys, and naughtily confound the photojournalists by firing their shutters.

Their expressions are notoriously inquisitive as they take pictures, simultaneous to the professionals, joining them mischievously in the process of photographic documentation.

"What are you planning to achieve from this journey?" the Comando Palomitas are asked.

Enthusiastically, they reply: Play!

Dozens of women, in dresses idiosyncratic to every single one of the Zapatista Caracoles – from the most diverse communities of the Tseltal jungle zone to the huipiles of the Highlands – with their lush black hair woven in elaborate braids and other traditional hairstyles, make of the dull boarding process a real party. All of them are seen with masks and acrylic face-shields.

The second part of the delegation departing in the afternoon wears black and brown caps, straw and traditional command hats composed of the emblematic colorful ribbons. There is not (unlike in other regions of the country) the slightest sign of obesity. Their bodies are shaped by work and discipline. Many wear black field boots. Others wear leather sandals.

Squadron 421 came out to see them off on the balcony of the Uníos office, where they barricaded themselves in Mexico City after 14 years since their last visit.

The first team of the airborne squad is made up of mostly women, girls, boys and families. They leave their suitcases and then are assisted by activists from the Anticapitalist University Network and the Zapatista Brigade in support of the EZLN.

Subcomandante Moisés is the first one to submit himself to the temperature checkup, and drops off his luggage. The atmosphere of the airport is completely altered.

It is inevitable to think that this Zapatista –who coordinates the airborne company, now with shirt, black cap and cell phone in his pocket– once held the position of mayor.

The coordination of the Extemporaneous

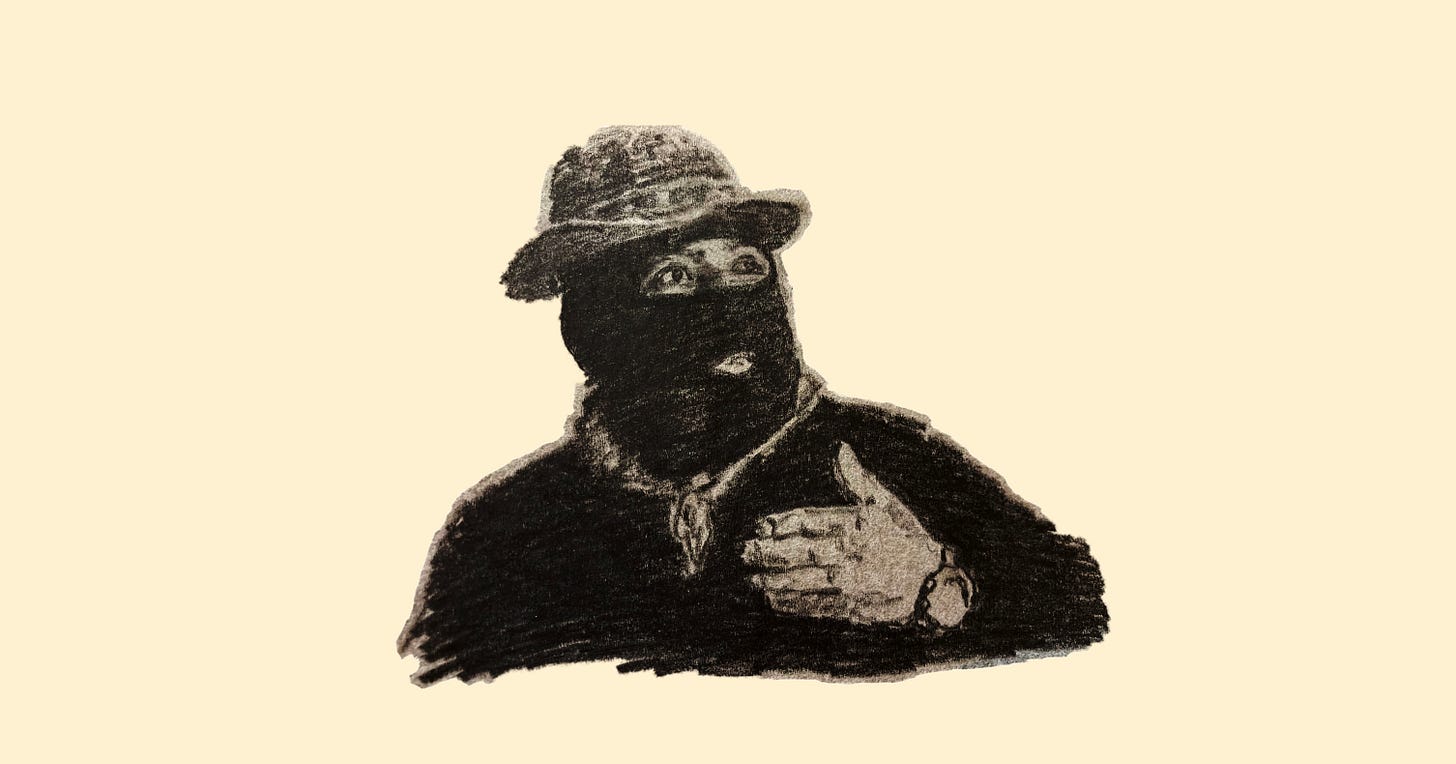

Two images, the same character, 27 years apart. The first is from February 16, 1994.

The then-Major Moisés, in military uniform and with a gun on his shoulder, delivered General Absalón Castellanos Domínguez, who had been taken prisoner by the rebels in the first days of the armed uprising.

[Note from taller ahuehuete: see footnote.]

The second is from September 13, 2021.

The now subcomandante, dressed in civilian clothes and a black cap, organizes the boarding of the plane that will take La Extemporánea Zapatista, bound for Austria.

Twenty-seven and a half years ago, Major Moisés was responsible for leading the ruthless ex-governor of Chiapas –the plantation owner who had until then trampled over lives and honor with impunity– to the community of Guadalupe Tepeyac.

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation condemned the State leader to bear on his shoulders the forgiveness* of those he had stepped on, humiliated, imprisoned and assassinated.

At that moment, in the presence of the press, the appointed government mediator Manuel Camacho and Bishop Samuel Ruíz, the Tseltal, who has participated in the Zapatista movement since 1983, explained the meaning of his cause, of military honor, and of the handover of the prisoner of war to the government.

Moi, as his comrades affectionately call him, speaks several languages. He organized the Tojolabal people of Las Margaritas during the uprising. His commander, Subcomandante Pedro, died in that municipality where he arranged the withdrawal of rebel troops.

A year later, when Ernesto Zedillo and Esteban Moctezuma organized the treason of February 9, Subcomandante Marcos was accompanied by Moisés.

With the oppressive recollections of life on the plantations, by then Lieutenant Colonel Moisés was appointed in 2005, responsible for international affairs of the Intergalactic, in the framework of the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandona Jungle.

Although he already knew many foreign solidarity comrades and activists, his relationship with them has increased since he was given the assignment.

And, as of today, in one of those twists of rebellious fate, he will meet in Europe with those with whom he has conversed for 27 years.

And here he is smiling, the current coordinator of La Extemporánea, Subcomandante Moisés, with almost four decades of unyielding resistance running through his veins, leading and organizing the disciplined Zapatista contingent, including minors from Comando Palomitas, across the arid jungle of marble, glass, storefronts and metal of the Benito Juárez airport.

Their procession shows ease, as if they were in the paths of misplacement in the canyons of the Lacandona.

Persevering and stubborn as they are in what they set their determination toward, the Zapatista peoples are today embarking on their journey to Europe.

They insisted on doing so, despite the Mexican government’s classist and racist passport issuing refusal. The Zapatistas were not recognized as Mexicans. As for excuses, the bureaucratic State apparatus insisted that because of the pandemic, the doors to Europe were closed.

The State later insisted that the vaccination process the Zapatistas had fulfilled in Mexico was not recognized by the health authorities on the other side of the Atlantic. Their voyage was thus delayed.

Nevertheless, they made it.